If you already donate large sums of money to charitable organizations or see a social need someone hasn’t met, it might be time to create a private foundation. Private foundations can provide consistent support to causes you care deeply about. In addition, a they can afford you both tax benefits and the prestige that comes with running a charitable organization in your name.

But what is a private foundation? Moreover, is the hassle of setting one up worth the return? In this article, we’ll explore the types, benefits, and rules. You can also find out how to start a charitable foundation of your own.

Defining a Private Foundation

A private foundation is an independent legal entity that is formed solely for charitable purposes, according to Foundation Source. Funding for a private organization generally comes from a single individual, a family, or a corporation.

Control of the private foundation can stay with the donor, depending on how one drafts the charter. So, forming one that gives more control to the founder/donor allows flexibility that entities like a public charity don’t allow. The donor determines the foundation’s mission, who is on the its board, where to invest the funds, and how and where the it gives funds away. Foundations can exist without a determined end date, allowing the donor to continue giving to it as long as it exists. Since it can exist in perpetuity, a foundation can become a living family heirloom that is passed down through generations.

The IRS considers many private foundations as nonprofits. They consider contributions to them as tax deductible, and thus can reduce the donor’s income tax. The donor can also avoid capital gains taxes, depending on the features of the property one contributes to the private foundation. Donors can enjoy a reduction or elimination of potential estate taxes on assets within the private foundation. The reason for this is that those assets become separate from a donor’s personal estate.

Some private foundation examples that currently exist include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, and the Coca-Cola Foundation, Inc.

Rules

In order for the IRS to classify on organization as a private foundation, it has several rules and regulations. The IRS considers every such organization that meets the requirements of a 501(c)(3) for tax exemption a private organization. That is, unless it is within one of the categories specifically excluded from the definition of that term. Excluded categories include institutions such as hospitals or universities, as well as those organizations with broad public support. The IRS also recognizes certain nonexempt charitable trusts as private foundations.

All of them must annually file the Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF, which is subject to public disclosure. Most domestic foundations have an excise tax on their investment income. Some foreign ones also have a tax on gross investment income from United States sources. These taxes must be reported on the Form 990-PF annually, or quarterly if the total tax for the year is $500 or more.

Private foundations have some restrictions on dealings between themselves and their substantial contributors. There are also limits on their holdings in private business. Private foundations must annually distribute income for charitable purposes. It is required that provisions on investments not jeopardize the carrying out of exempt purposes. Provisions must also be in place to assure that expenditures further exempt purposes. Violations of these provisions result in taxes and penalties. In some cases, those penalties may extend to its managers, substantial contributors, and certain related persons.

A private foundation must follow the regulations described in 501(c)(3) in addition to the regulations mentioned above. If not, then the organization is not tax exempt and its contributions are not tax deductible.

Types of Foundations

There are several different types that that fall under the “private foundations” umbrella. The Council of Foundations lists the main five types that are used to help others understand how a particular type operates.

- Corporate foundations, also sometimes called company-sponsored foundations, are private foundations that a corporation creates and funds. It is a separate entity from the business but has close ties. Grants from this type of entity generally go to communities or activities within the company’s field.

- Family foundations are funded by an endowment from a family. As such, the family members of the donor typically play a large role in its governance.

- International foundations are those that are based outside of the United States. These private foundations make grants both inside and outside their own countries. The term usually applies to those those that engage in cross-border giving. Under U.S. law, contributions to these foreign-based foundations from U.S. donors and corporations are not eligible for charitable tax deductions.

- Private operating foundations are those that focus on operating their own charitable programs, although some make grants as well. Unlike the other types, a private operating foundation is a legal classification under the Internal Revenue Code, although it continues to follow most of the same rules as the other types. Private operating foundations are required to spend a certain portion of their assets on charitable activities every year, whereas a private non-operating foundation is required to pay 5 percent or more of their assets on grants each year. Examples can include museums, zoos, research facilities, and libraries.

- Independent foundations are not governed under a benefactor, the benefactor’s family, or a corporation, like most other private foundation types. Instead, endowments fund this version of the entity through a single source like an individual or group of individuals.

Jurisdictions

We can form foundations in any U.S. state and many foreign jurisdictions. Many offshore foundations offer additional benefits such as asset protection and may offer substantial tax benefits. For the tax benefits, be sure to keep the counsel of an experienced, licensed accountant.

Domestic Foundations

As far as domestic foundations, we like Wyoming and Delaware because of the cost and ease of formation. In addition, the regulations are not overburdensome. Some states have mandatory audits, including Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Some states in particular micromanage foundations. California has especially burdensome regulations. For example, nonprofit organizations need to with the Attorney General, the Secretary of State, and the Franchise Tax Board. California will not allow non-voting board members. Another state, Massachusetts, requires the approval of a judge for even simple acts such as dissolutions and mergers with other nonprofits.

Offshore Foundations

Onerous domestic regulation is one reason offshore foundations are often much more favorable. A great example is the Nevis foundation. Rather then saddle you with rigid regulations, Nevis multiform foundations can also act as a company, partnership and trust.

The Cook Islands foundation is another great example of an offshore legal tool. Its laws stem from other long standing foundation jurisdictions such as Guernsey and the Isle of Man. The laws have special provisions that give outstanding client planning options and more straightforward asset protection provisions in addition to strict privacy regulations.

Private Foundation vs Public Charity

Although they are both operate to support charitable purposes, a private foundation and a public charity have a lot of differences. As 501c3.org explains, the main difference is source of their funding. A public charity earns its funding through public contributions. Those contributions can come in the form of grants from individuals, the government, or private foundations. A private foundation, on the other hand, does not solicit funds from the public. Its main funding usually comes from a single source, like an individual, family, or corporation.

In distributing funds, some public charities give grants. Most of them, however, use their assets to provide direct service or participate in other tax-exempt activities. Conversely, most private foundations use their funds solely for making grants to other nonprofit organizations. In order to keep their tax-exempt status with the IRS, private foundations support charitable, educational, religious, or other public entities. These entities must have 501(c)(3) status or have a fiscally organization that sponsors them. In managing all assets, public charities are required to be governed by a board of directors that is reflective of the constituency that it serves. On the other hand, donors or people chosen by the donors solely govern a private foundation.

Another differences between these two entities is what information they share with the public. The giving history of private foundations is public record. The principles of the organization must disclose all grantees and grant amounts to the IRS. There is not a similar requirement for a public charity to provide its giving history to the public. Access to grants data for a public charity is dependent on how much the funder is willing to share on its Form 990, website, or other methods of communication.

Setting Up a Private Foundation

While many people contribute to charitable causes without creating a private foundation, there are many good reasons to set one up. Investopedia explains that a foundation allows the donor to fund a cause more consistently to provide cumulative benefits to the recipients. Some families also choose private these tools to create a family legacy. Thus, the organization encourages members of the family to participate in funding a common cause. The third most common reason for choosing a private foundation is that it comes with many tax benefits.

To set up a private foundation, you should first determine the organization’s purpose and what guidelines it will follow to make grants. Next, you should decide on the structure of your foundation, whether that is a charitable trust or a nonprofit corporation. Charitable trusts are easier to establish and operate, but don’t have as much legal protection as a nonprofit corporation. Nonprofits have stricter operating requirements, but they limit personal liability and allow more flexibility in how their funds are used.

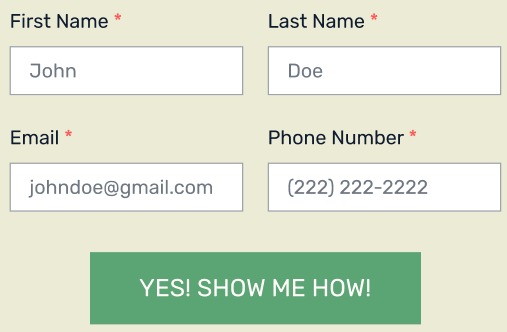

After you’ve chosen a structure, you’ll need to apply for an Employee Identification Number (EIN) from the IRS. There is also paperwork to fill out, including a Form 1023, Application for Recognition of Exemption Under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code and its supporting documentation. There may be other documentation required by your state in order to obtain tax-exempt status.

Foundations for Asset Protection

Incidentally, some promoters espouse the use of foundations for asset protection from lawsuits. After all, their proponents argue, once you put assets into a foundation they are no longer yours. Thus, your creditor cannot take them. Plus, they proclaim, you get to take a tax deduction for contributing assets to a foundation.

Whereas that my be true in some cases, try holding on to those benefits once you use the money to pay your bills, buy a car or pay for a home. Once a judge sees you using foundation assets for your own purposes, he or she will likely propose that your creditors can do the same. Thus, the asset protection of the foundation goes out the window.

Moreover, do you hear that hissing sound? That is the sound of money leaking out of your foundation in order to retain its tax-free status. That is, if you are a U.S. person, you must pay out five percent of trust assets for philanthropic purposes each year in order to retain its charitable standing. Let’s see how that affects your ROI. Plus, there are severe restrictions on foundation assets providing benefits for you, as an individual, if you are the founder of the organization.

Compare to an Asset Protection Trust

We suggest you read our article comparing foundation vs. trust. Therein, you will see that using a foundation for asset protection is like putting a square peg in a round hole. Its purpose is charity, not asset protection. If you want asset protection you are better off setting up an asset protection trust. With an asset protection trust, you can eat your cake and have it too. On one hand, you can enjoy case law proven asset protection. On the other, when set up properly in choice jurisdictions, you still get to relish in the fruits of your well-protected labor. That is, the money is in the trust for your use within the bounds of prudent asset protection parameters that the trustee provides.

So, a foundation for asset protection may work. The problems are glaring, however, when we shine a bright light on the downsides. It is extremely an extremely unattractive option if you intend to use the money for yourself in the future. You almost certainly lose the tax benefits if you spend foundation assets on personal expenses. Plus, the case law history on how well it works to protect assets from lawsuits is sorely lacking. For asset protection trusts in offshore jurisdictions such as the Cook Islands trust and Nevis trust, the results are stellar. We like to bet our money on observable history, not theory. So, our opinion is to use a foundation for charitable purposes, as is was designed. Then, use an asset protection trust for how the law intended, for asset protection.

Get the Most of Your Philanthropic Goals

You’re already trying to make the world a better place with your charitable contributions, but it doesn’t have to stop with the occasional check. A private foundation can be a rewarding endeavor that can make a huge impact.

Creating and maintaining a private foundation is a lot of work, though, especially with all the guidelines you have to follow. That’s where you need the experts. We’ll guide you through the process of how to start a foundation to help others and help you understand your options. Contact us today to secure your legacy of giving.